As logic stands, every story has to come from somewhere. Shakespeare, for instance, stole the plots of bad plays from lesser known playwrights and rewrote them until they’re canonical works of English literature. Balzac would get amped up on over 10 espressos a day and eavesdrop on other people’s conversations in the local café (which explains how he wrote 100 novels in his lifetime). And Coleridge tended to ingest an ungodly amount of opiates and hope no one from Porlock showed up for a few days. But these men were geniuses whose individual talents are unparalleled throughout history. What about the rest of us? The tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to have one idea that doesn’t objectively suck? What are we supposed to do? More importantly, what’s a young playwright supposed to do when he has a theater booked in New York in six months time, but no play to show the company?

This is the question I’m exploring.

The American Story Project’s last original play (and the only thing I’ve ever had anyone else produce), the critically acclaimed We Can’t Reach You, Hartford came about when I had a nightmare one night about a circus fire I had learned about in elementary school. And while it took at least four rewrites before the scattered rough chuckles really began to work in a play obsessed with the death of small children, as far as the brainstorming process goes, it was a relatively painless ordeal. But that was a fluke and I knew it wasn’t going to happen like that again. A man only has a finite number of repressed pre-adolescent memories suitable for adaptation into a piece of semi-documentary theater. This time around, I was going to have to work for my writing credit. But like hell was I going to do it alone. I had an entire theater company to do my dirty work for me.

The path that finally led to Daguerreotype, the American Story Project’s 2007 production, was long and certainly rather strange. It began in September with the ambiguous goals of presenting something political and something about surveillance. This soon turned into the kind of happy melee where great ideas are born, an entire company throwing ideas back in forth, sometimes in dialogue, sometimes blissfully unaware that any dialogue was taking place. The ideas came from our interests, our concerns, our secret wishes and fears, our curiosity, and our sincere desire to find a way to entertain entire busloads of surly Scots.

At one point, our ever shifting sense of the play included:

Richard Nixon

John Walker Lindh

Foucault’s work on panopticons

Shoes, lots of shoes

Rabbi Akiba

Castle Thunder

Infinite variations upon This American Life

the influenza epidemic of 1918

Julius Caesar (the play, not the man. Well, the man, but in the play.)

Alexander Scriabin

and probably some other things I’ve forgotten about along the way.

How this all adds up to the Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, I’ll never know. The more I think about it, the less sure I am about how we got onto Mathew Brady in the first place. For me, a map of the thought process that led us to Daguerrotype resembles nothing so much as a Ven diagram. And I imagine each of us involved in the development would have a completely different story about how this all came about, which is somehow fitting for a group of artists who find their inspiration in the problems of history’s creation. Nonetheless, somehow we’ve arrived here, at this time, at this place, and with this man. How this all adds up to the Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, I’ll never know. The more I think about it, the less sure I am about how we got onto Mathew Brady in the first place. For me, a map of the thought process that led us to Daguerrotype resembles nothing so much as a Ven diagram. And I imagine each of us involved in the development would have a completely different story about how this all came about, which is somehow fitting for a group of artists who find their inspiration in the problems of history’s creation. Nonetheless, somehow we’ve arrived here, at this time, at this place, and with this man.

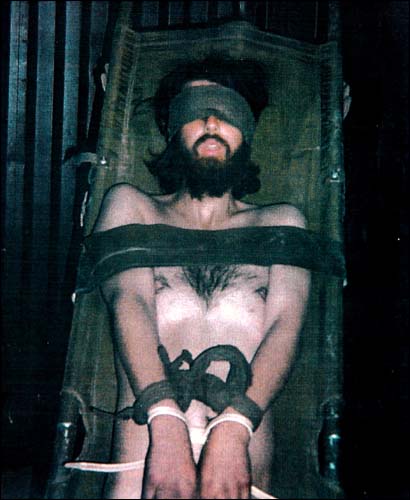

And let me tell you, if beards are any indication, its going to be a wild ride. |